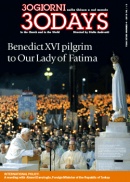

SPANISH COLLEGE

The many “Spains” of the San José

Founded in 1892 by the priest Manuel Domingo y Sol the Spanish College of San José has to date hosted 3,400 young seminarians and priests: 120 were appointed bishops, 8 created cardinals. Today 87 priests from 37 dioceses in Spain and from six other countries of the world live in Via di Torre Rossa

by Pina Baglioni

![Father Herrera Fraile, rector of the Pontifical Spanish College, next to the bust of the founder, Blessed Manuel Domingo y Sol in the atrium of the College [© Paolo Galosi]](/upload/articoli_immagini_interne/1279201825316.jpg)

Father Herrera Fraile, rector of the Pontifical Spanish College, next to the bust of the founder, Blessed Manuel Domingo y Sol in the atrium of the College [© Paolo Galosi]

Right at the beginning of the Via di Torre Rossa, the imposing Pontificio Colegio Español de San José nestles between Villa Carpegna and the splendid Abbey of St Jerome in Urbe, on an area of 220,000 square meters of mediterranean scrub belonging to the Spanish Bishops’ Conference.

When you enter the front door, a wall painting summarizes the history of the Church of Spain through the stylized figures of its great saints, kings and queens. The position of honor is taken by the bust of Blessed Manuel Domingo y Sol, the simple priest of Tortosa who on 1 April 1892 founded the San José. For Mosén Sol, “Reverend Sun” – as he was affectionately known – it was the dream of a lifetime to establish a college in Rome with the aid of a group of priest friends, who in July 1883, he had gathered together in the diocesan Fraternity of Worker Priests of the Heart of Jesus. He was to entrust the direction of the San José to them. “Not worker-priests but workers in the vineyard of the Lord”, explained Father Mariano Herrera Fraile, rector of San José for the last three years. When he led me into his study, I couldn’t fail to see, in a corner, a large statue of the Curé d’Ars. “I wanted him near me in this Year of the Priest. It comes from the old site of the College, Palazzo Altemps, from the private room of Cardinal Merry del Val, one of the great protectors of our College”.

Father Herrera Fraile is 61 years old, a priest for 36. A life spent in training future priests first in the seminary of Zaragoza, then in Segovia. Then another 17 years in Toledo, at the minor seminary, then in the major, of which he became rector. From 1997 to 2003 he was at the San José as spiritual director, then moved, again as spiritual director, to the Secretariat for Seminaries at the Spanish Episcopal Conference. Three years ago, the Congregation for Catholic Education and the Spanish Episcopal Conference appointed him rector of the College, which Father Herrera Fraile directs along with four other members of the Fraternity of worker-priests of the Heart of Jesus

At the moment the College is a building site: bulldozers and workmen are restoring internal and external areas of the building. “We have to rationalize and cut down space. But we continue to organize conferences and courses in these huge surroundings – as, for example, the course for trainers for major seminaries, or ‘updating priesthood’ for the priests of the Spanish dioceses”, says Father Herrera Fraile. “Then we have to prepare spiritual exercises, which will also involve students from all the other pontifical colleges of Rome, and a series of conferences devoted to the Year of the Priest”.

The busy forge of courses and conferences in Via di Torre Rossa is also a point of reference for Spanish bishops and cardinals visiting Rome. In particular, its patrons, such as the Archbishop of Seville, Monsignor Juan José Asenjo Pelegrina, Monsignor Braulio Rodríguez Plaza, Archbishop of Toledo, Cardinal Antonio María Rouco Varela, Archbishop of Madrid and president of the Spanish Episcopal Conference.

“Precisely within these walls the Study Commission of the encyclical Humanae Vitae met. And before that, most of the Spanish bishops and cardinals present at the Second Vatican Council stayed here: almost all of them former students”, says seventy year-old Don Vicente Cárcel Ortí, who has lodged in the College, since he came to Rome from Manises in the diocese of Valencia in his early twenties, already a priest, to finish his studies. In the days when the site of the Spanish College was still Palazzo Altemps.

Don Vicente Cárcel Ortí today works with the parish of Pope St Martin I in the Appio Latino district, but for 37 years, up to 2005, he was Head of Chancery of the Supreme Court of the Apostolic Signet. A historian whose field is the contemporary Spanish Church, he had the privilege of being the first Spaniard to view the documentation on the pontificate of Pius XI made available to scholars on 18 September 2006. He is the editor of the unabridged edition of Documentos del Archivo Secreto Vaticano sobre la Segunda República y la guerra civil (1931-1939) presently being published by the Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos (BAC). Who could be better qualified to preserve the historical memory of the College, of which he has written, with Don Lope Rubio Parrado, the previous rector, a volume that is also in the process of publication.

I met him with with twenty-nine year-old David Varela Vázquez, a Galician, doing his doctorate in dogmatic theology at the Gregorian University with a thesis in Christology. Ordained in 2006 in Lugo in his diocese, he confided that from childhood he nourished the desire to become a priest, not least because of Pope John Paul II, keeping all the newspaper clippings about him. He explained that, differently than almost all colleges in Rome, which, normally, “lend” their priests to city parishes, there is no such custom at the Spanish college. “The main reason we’re here is to study. Not least because our bishops invest a lot in us”. He is very grateful to Rome: he arrived here a deacon and is now a priest. “Only in this city do you realize how great the Church is: closeness to the Pope, the remains of the martyrs, the beauty of the city help you understand what catholicity is”.

![The Mass for the inauguration of the academic year 2008-2009 [© Pontifical Spanish College]](/upload/articoli_immagini_interne/1279201825332.jpg)

The Mass for the inauguration of the academic year 2008-2009 [© Pontifical Spanish College]

Father David Vázquez Varela is one of 87 diocesan priests staying at the San José. They come from 43 dioceses, including 37 in Spain. The Congo, Venezuela, Brazil, Chile, Zaire and Puerto Rico are the other countries represented. Twenty-four of these priests are going to get a doctorate, the other a licentiate. “Seminarians haven’t been coming for some time. At most there’s a deacon who becomes a priest during the year. The priests that come to the college are experts. They’ve already been parish priests or teachers in the diocesan seminaries and want to further their studies”, Don Vicente Cárcel Ortí explained. “In my day we went to study at the Gregorian only, not least because the other universities were founded later. Now, everyone goes everywhere, even if the majority continue to favor the University in Piazza della Pilotta: as many as 48 just in this academic year. The subjects most followed are Dogmatic Theology and Canon Law”. Back in Spain, they will all go to fill posts of some responsibility: “In my diocese, in Valencia alone, of those back from Rome, one has become rector of a Seminary, another vicar general”.

Nearly all the guests at San José are quite grown up. Twenty-seven of them are between 29 and 33, twenty-six between 34 and 38, eleven between 39 and 43, nine between 44 and 48 and two between 49 and 53. Only eleven of them are between 24 and 28. And to provide a complete picture one must go further: Father Augustín Sánchez Pérez is 63 years old and about to gain his doctorate in Canon Law at the Lateran, having spent a lifetime at Las Palmas in Canary Islands, as rector of the seminary.

Every day at San José Lauds is at 7 o’clock. Then the dash to lectures. Back home, lunch all together, Italian style. Even so, once or twice a week, the Italian cooks take pity and offer paella, a famous dish from Valencia, a symbol of Spanish cuisine. Then study again and other pauses for prayer. Mass is at 19.45. After that, all to dinner. At most, a few games of soccer during the week. And the arguments between fans of Real Madrid and Barça.

“I and the four brethren who share responsibility for the College aim at supporting our priests and there is a family atmosphere here in which everyone can count on the others. In short, a priestly fraternity as conceived and worked for by Blessed Manuel Domingo y Sol”, says Father Herrera Fraile. “We share out our tasks here: there is a Student Council which, through various committees, deals with the various needs of the house: from liturgy to sports, from the library to cultural activities”.

I ask if these very studious Spanish priests have a little time off to visit the city. “Of course: at weekends, when possible, they go around to visit the wonders of Rome. Many years ago we made the visit to the Seven Churches. And twice we have looked at the places connected with St Paul. Every now and again we go to Subiaco, near Rome, to visit the monasteries of St Benedict and St Scholastica”.

While expressing optimism for a small increase in seminarians in recent years, the Spanish bishops attribute the long-running crisis of vocations in Spain to falling birth rates, the secularization of society, the unfavorable family environment. “The real problem is the lack of young men entering the seminary, also due to the increased aging of the population. As for us, we’re doing a lot of work on the pastoral for vocations”, says Father Herrera Fraile. “There’s a certain vitality in the seminaries of all the dioceses. The political, social, family situation is what it is. But we don’t despair. One must also say that many, many people still live and feel Christian history and tradition in the depths of their hearts. Let’s hope, then, that Providence stirs new vocations”.

A sign of hope, again from what one can learn from the site of the Episcopal Conference, are the growing numbers in Spanish seminaries of young Latin Americans, Africans and sons of immigrants.

“Spain has always been considered a super Catholic country: it’s a myth. The consequences of such alleged Catholicism are visible to everyone. Especially in recent decades”. Don Cárcel Ortí starts from a different angle to explain the situation in his country: “There is another aspect to consider: outside observers talk of ‘Spain’. The situation is more complex. In reality Spain does not exist as a unit: that is another myth hard to die. There is a wide diversity of regions, although the state is a single entity. Take, for example this college, where all the autonomous communities live together: we all respect and live in total harmony, united in obedience to the Church and the Pope. Never forget, however, that there are many ‘Spains’ and we must reckon with all these realities. In dialogue, we hope, without unnecessary and damaging disputes”.

The young graduate student, Don David Varela Vázquez, meanwhile, does not seem particularly impressed by the situation just described: “It’s very clear to me that the only thing required of me will be to hand on, to proclaim the beauty of Christianity to the people I meet. I firmly believe that Christianity can still attract people’s hearts. As a student of theology I have been following the teaching of Benedict XVI: a great theologian who expresses himself in clear and simple fashion. And he chose as emblem for the Year of the Priest a humble priest, the Curé d’Ars. I was much struck by that. What will happen to me once back in Spain, I haven’t the faintest idea. I know it’s pointless imagining extraordinary effort of will: our life is always the work of Another”.