«IUSTITIA ET PAX». Interview with Cardinal Peter Kodwo Appiah Turkson

The way of Africa, or Africa on the way

A meeting with the President of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace: the crisis in Nigeria and in the north-east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The external debt that strangles the governments of the African continent. But also the progress and hopes of what the Pope has called the “healthy lung of humanity”

Interview with Cardinal Peter Kodwo Appiah Turkson by Roberto Rotondo and Davide Malacaria

Cardinal Peter Kodwo Appiah Turkson, Ghanaian, President of the Pontifical

Council for Justice and Peace for the past six months, is the youngest African

cardinal and the most senior personage in the Vatican Curia from the African

continent. Born in Wassaw Nsuta, western Ghana, he was ordained priest for the

diocese of Cape Coast in 1975, of which he later became archbishop in 1992. He

was president of the Episcopal Conference of Ghana from 1997 to 2005. He

studied in the United States and at the Biblical Institute in Rome. He speaks

English, French, Italian and German. He knows Hebrew, Latin and Ancient Greek.

Created cardinal in 2003 – the first Ghanaian cardinal in history – he was general spokesman of the special Synod for Africa at the end of 2009. We

took stock with him. He told us of his wish to bring to his new experience in

Rome the “great sense of solidarity and pursuit of justice” of the African people, and we discussed some serious, unfortunately “chronic”, problems of sub-Saharan Africa. We began from his last trip to Nigeria.

![Cardinal Peter Kodwo Appiah Turkson [© Reuters/Contrasto]](/upload/articoli_immagini_interne/1279200051941.jpg)

In March you traveled to Nigeria, just days after the massacre of hundreds of

people in three farmers’ villages, mostly Catholics, in the Diocese of Jos. What idea did you form of

the situation after the attacks of 7 March, which initially had been hastily

attributed to the rivalry between Christians and Muslims?

PETER KODWO APPIAH TURKSON: When I received the news of the villages taken by assault at night and hundreds of women and children killed, I immediately thought of leaving to help the Archbishop of Jos, Bishop Ignatius Kaigama, to restore calm and to curb those who, wanting revenge, risked fomenting a dramatic spiral of violence. I know Kaigama well, he is also president of the Nigerian Council for Interreligious Dialogue and has always sought to promote peace, but in those days he was left almost alone to urge people to remain calm. From the first moment it became clear that it was a terrible tribal revenge and L’Osservatore Romano also ruled out the religious origin but, despite this, the idea that the root of the violence in Nigeria was the clash between Muslims and Christians had already traveled the world on the mass media.

And instead?

TURKSON: Instead, tragically, it was a reprisal of the Fulani herdsmen, nomads and mostly Muslim, against the farmers, settled and mostly Christians. The cause of reprisal? The killing of some cattle and a few episodes of violence suffered by the Fulani herdsmen, accused by the farmers of ruining crops with their herds, which, because of drought, had been pushed south into cultivated areas. The fact is that for the Fulani livestock are more valuable than life, but also for the farmers the harvest is a matter of life or death.

A tragic war between the poor...

TURKSON: Yes, it is a problem that has been going on for years. The local Church has been trying in every way to restore harmony, but until the government of the region and the central government succeed in guaranteeing security and justice, the situation will always remain at risk. Precisely for this reason, on 19 March, having presided over a Mass celebrated in memory of the victims, during which I also read a message from Benedict XVI, we met the government officials of the region and we reiterated that all these poor people – who during each mass pray for the government, for the State, for the President – have the right to be able to sleep in their beds safely. The most striking thing, in fact, is that the attacks on the villages occurred at two in the morning when people were asleep at home, precisely in order to cause the most damage. It was essentially a calculated revenge, not an irrational explosion of violence.

And on the Muslim side was there no desire to calm spirits?

TURKSON: In Jos I also met with the Muslim leader Amil who works closely with Kaigama. They both want to help generate peace but on both sides there are those who rebuff the attempts: some Christians say that the archbishop is too trusting of Muslims and some Muslims say that the Emir will eventually be converted to Christianity by the bishop. But their way is the only chance for coexistence, peace and development in the area. They have also talked with the Sultan of Sokoto, who is the highest authority of Islam in Nigeria, and we hope that many others will decide to follow the path of dialogue.

Is the mistaken attribution of the clashes to a war of religion also the result of the inability on our part to listen to and understand what is happening in Africa?

TURKSON: Yes, that is so. Seen from here, everything seems just “Africa”: starving Africa, Africa victim of tribal violence, of the struggle for natural resources... But in sub-Saharan Africa there are 48 nation states, each with its own particular situation, its own problems, its own dramas, its own progress. Respecting Africa, means first of all learning not to generalize. In Ghana, where I was born, for example, the president of Parliament, the Justice Minister and police chief are women, but this certainly doesn’t mean that Africa has learned to value the role of women. So the problems relative to religious ethnic and demographic balances change from country to country: Muslims and Christians in Nigeria are numerically equal, in Sierra Leone Muslims are in the majority. In Ghana, Islam is a minority, accounting for 18 percent of the population, so we have a problem that others don’t: there are groups that are not happy with the religious and ethnic balance reached in the country which allows coexistence. And in recent years these groups have implemented strategies to change the demographic balance. I’m not launching a crusade, but we are aware that the phenomenon exists and, as both the French and Italians say, a person forewarned...

The situation of permanent crisis in the north-eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo (which is an area of Catholic majority) remains an open wound on the African continent. Why can this situation of continuous instability not be overcome? Is it only a problem of the struggle to exploit the immense natural resources?

TURKSON: The struggle for resources is an important factor in the crisis, but is not the only one. Another factor is the lack of infrastructure such as roads or bridges: in a country so large, this means the central power is very distant and slow to take action. And then the various tribal and ethnic affiliations are a further element of instability when, partly because of the interferences of external forces in Congo, they are no longer able to find a balance between themselves. Part of the Congolese people, in fact, consider themselves Rwandan or Burundian. This is a common problem in many parts of Africa, where borders divide tribes, ethnic groups or homogeneous groups by history and traditions. The same thing happens with us here in Ghana: there is a village along the border with Togo in which a road is the dividing line. The villagers who are on one side of the road are Ghanaians, the other ones Togolese. With us it is just a bizarre situation, but in the area of Kivu, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, it has taken on dramatic aspects. Also because those who want to make away with the immense natural resources of the area, whether gold or diamonds, timber or coltan, have every interest in a state of chaos reigning permanently. When there is anarchy, confusion, even a small group of armed men can terrorize entire villages, open illegal mines, carry off everything. Only a strong central government can solve the situation piecemeal.

![Congolese Catholics during the Palm Sunday procession [© M.Merletto/Nigrizia]](/upload/articoli_immagini_interne/1279200004410.jpg)

Speaking of sub-Saharan Africa’s problems you said that some men of the African political and business class

are inadequate and, at times, even corrupt and accomplices of those outside

lobbies who exploit the continent...

to make huge holes on the surface of the ground, wiping out the forest. Nobody cares if one day instead of forest and farmland we will have only large empty craters because the government needs financial resources urgently and whatever brings money in the short term is preferable to long-term projects.

Because of this the Holy Father’s Message for peace this year, which speaks of solidarity with the environment and solidarity between the present and future generations, is very real and has political, social and economic implications very much felt in Africa.

Ten years ago, in 2000, there was a great campaign for the cancellation of the foreign debt of developing countries. With what results?

TURKSON: Debt is not the biggest problem: if they cancel our debts but we don’t have the means to produce goods and merchandise, we’ll never be able to create capital. We’ll get into debt again.

But right now the African countries can barely pay the interest, without ever managing to pay off the debt...

TURKSON: It would be more to the point if the governments of African countries increased productive and industrial capacity, because if we continue just to sell raw materials or unprocessed products we’ll never succeed in creating a strong economy and always be strangled by debt. Ghana, for example, is among the largest producers of cocoa in the world, but how many chocolate factories are there in Ghana? We grow tomatoes in abundance, but how many canning factories are there? It’s mainly from the manufacturing industry that wealth and stable development can come, but it’s precisely there that Africa is very weak. Only if we convert ox leather into shoes will we emerge from this vicious cycle of loans and interest.

At the Special Synod for Africa Pope Benedict XVI described the continent as the healthy lung of mankind. But what can Africa give the world?

TURKSON: The Pope was referring to Christian, religious and human values of Africa and said that we must be careful not to let this lung of humanity grow sick. It is a healthy lung when it looks to those values of the Evangelium Vitae that Pope John Paul II talked about; and the source of disease is secularism and relativism, from which Africa, so far at least, seems safe, even though we live in a globalized world and there are many threats that come to us in ways that, in themselves, are very positive. For example the Internet, through which everything reaches our young people and without any mediation. The Net brings many fine things, but you can also access sites that show you how to build a bomb and incite hatred.

You are very attached to Ghana and Africa, so much so that they say the Pope had to struggle quite a bit to persuade you to come to Rome. What of your experience as pastor have you brought with you?

TURKSON: I think I did the minimum I had to do in Cape Coast, by God’s grace and help. I was the successor of a very famous and much loved archbishop, John Kodwo Amissah, the first native archbishop of Ghana and perhaps the first African archbishop in all West Africa. He was a key figure in the political process that would have led to independence from England. I remember that at the time of my ordination, they asked me whether I felt cut out to succeed such a charismatic figure and I answered with an old saying that the only shoes I wear are my own because the others may be either too large or too small. Everything would depend on what the Lord would allow me to do. Anyway I was there from 1993 up to 2010, and fundamentally I tried to do two things: invest heavily in training priests – we have a good major seminary with capable teachers and many priests come out of it – and seek to involve young people, through initiatives also related to school, to bring them back to the Catholic Church.

Your father was Catholic and your mother was Methodist. How did your priestly vocation arrive?

TURKSON: My mother was a Methodist but converted to Catholicism when she married my father. The story of my vocation is very simple. Maybe every priestly vocation comes out of an apparently trivial reason, but then grows and clarifies in the seminary. A vocation is a bit like the starter mechanism of a car, the spark that starts the engine, and the story of my vocation is something similar. The original reason why I entered the seminary was the figure of a Dutch priest who came every two months to celebrate Mass in the small town where I grew up. Dad was a carpenter and ours was a small town near a manganese mine. There was no resident parish priest and I remember this priest who came now and then, he would sleep in the church, and in the morning was always there prompt waiting for people to come to Mass. I was struck by that, and later, when I reached secondary school age, I asked to join the minor seminary. I always tell the seminarians: the story of our vocation begins with something very small, but the seminary, as I mentioned, is the place where the vocation grows and becomes clear.

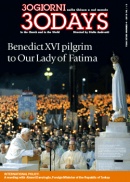

![Turkson speaking with Pope Benedict XVI as president of “Iustitia et Pax”, 26 March 2010 [© Osservatore Romano]](/upload/articoli_immagini_interne/1279200004441.jpg)

The fact that it was a Dutch priest brings to mind that Africa today, in sending

many priests to Europe and the United States, is giving back what it received

in the past...

TURKSON: We have a proverb that says: ‘If someone takes care to see your teeth grow, it’s up to you to take care of him when he loses his’. Europe brought us the Christian faith and we welcomed it. And the more alive that faith is the more grateful we are to those who brought it. Out of that gratitude, if now in Europe or the US a church is likely to close due to a lack of priests, we are ready to help keep it open, always hoping that with the help of the Lord, things will change. In Ghana, there is no longer any missionary order, apart from some native Franciscans, and two or three American Jesuits who teach in our seminary, however, there are many Ghanaian priests throughout the world.

The social encyclical of the Pope’s Caritas in veritate, on the guidelines of which the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace is working, was published in a particular historical period when the global economic crisis highlighted the excesses of a financial system without regulation and the injustices resulting. Almost a year after its publication, is the encyclical today a useful tool for thinking how to get out of the crisis?

TURKSON: As we know, Caritas in veritate was drafted in view of the fortieth anniversary of Populorum Progressio and its release was delayed so that it could be recast in the light of the crisis that had hit financial markets. Whether it is useful or not is up to the reader’s judgment, but the intent was not to provide a new economic recipe, but rather to stress the need of introducing mankind itself as the basic principle of economics, of the financial system but also of technological progress. Development that doesn’t help and encourage the development of the person can’t be considered true development. So it was a call to humanize the economy and then, since the world is becoming increasingly globalized and no one country can tackle the situation alone, the Holy Father asked whether it wasn’t time to develop a world body to steer globalization. I know that some people in the US have criticized the Pope accusing him of wanting to be the spiritual leader of a world government, but that’s nonsense. All one has to do is read what is happening in the world these days: nobody is strong enough to face these phenomena and these crises alone.

![Cardinal Peter Kodwo Appiah Turkson [© Reuters/Contrasto]](/upload/articoli_immagini_interne/1279200051941.jpg)

Cardinal Peter Kodwo Appiah Turkson [© Reuters/Contrasto]

PETER KODWO APPIAH TURKSON: When I received the news of the villages taken by assault at night and hundreds of women and children killed, I immediately thought of leaving to help the Archbishop of Jos, Bishop Ignatius Kaigama, to restore calm and to curb those who, wanting revenge, risked fomenting a dramatic spiral of violence. I know Kaigama well, he is also president of the Nigerian Council for Interreligious Dialogue and has always sought to promote peace, but in those days he was left almost alone to urge people to remain calm. From the first moment it became clear that it was a terrible tribal revenge and L’Osservatore Romano also ruled out the religious origin but, despite this, the idea that the root of the violence in Nigeria was the clash between Muslims and Christians had already traveled the world on the mass media.

And instead?

TURKSON: Instead, tragically, it was a reprisal of the Fulani herdsmen, nomads and mostly Muslim, against the farmers, settled and mostly Christians. The cause of reprisal? The killing of some cattle and a few episodes of violence suffered by the Fulani herdsmen, accused by the farmers of ruining crops with their herds, which, because of drought, had been pushed south into cultivated areas. The fact is that for the Fulani livestock are more valuable than life, but also for the farmers the harvest is a matter of life or death.

A tragic war between the poor...

TURKSON: Yes, it is a problem that has been going on for years. The local Church has been trying in every way to restore harmony, but until the government of the region and the central government succeed in guaranteeing security and justice, the situation will always remain at risk. Precisely for this reason, on 19 March, having presided over a Mass celebrated in memory of the victims, during which I also read a message from Benedict XVI, we met the government officials of the region and we reiterated that all these poor people – who during each mass pray for the government, for the State, for the President – have the right to be able to sleep in their beds safely. The most striking thing, in fact, is that the attacks on the villages occurred at two in the morning when people were asleep at home, precisely in order to cause the most damage. It was essentially a calculated revenge, not an irrational explosion of violence.

And on the Muslim side was there no desire to calm spirits?

TURKSON: In Jos I also met with the Muslim leader Amil who works closely with Kaigama. They both want to help generate peace but on both sides there are those who rebuff the attempts: some Christians say that the archbishop is too trusting of Muslims and some Muslims say that the Emir will eventually be converted to Christianity by the bishop. But their way is the only chance for coexistence, peace and development in the area. They have also talked with the Sultan of Sokoto, who is the highest authority of Islam in Nigeria, and we hope that many others will decide to follow the path of dialogue.

Is the mistaken attribution of the clashes to a war of religion also the result of the inability on our part to listen to and understand what is happening in Africa?

TURKSON: Yes, that is so. Seen from here, everything seems just “Africa”: starving Africa, Africa victim of tribal violence, of the struggle for natural resources... But in sub-Saharan Africa there are 48 nation states, each with its own particular situation, its own problems, its own dramas, its own progress. Respecting Africa, means first of all learning not to generalize. In Ghana, where I was born, for example, the president of Parliament, the Justice Minister and police chief are women, but this certainly doesn’t mean that Africa has learned to value the role of women. So the problems relative to religious ethnic and demographic balances change from country to country: Muslims and Christians in Nigeria are numerically equal, in Sierra Leone Muslims are in the majority. In Ghana, Islam is a minority, accounting for 18 percent of the population, so we have a problem that others don’t: there are groups that are not happy with the religious and ethnic balance reached in the country which allows coexistence. And in recent years these groups have implemented strategies to change the demographic balance. I’m not launching a crusade, but we are aware that the phenomenon exists and, as both the French and Italians say, a person forewarned...

The situation of permanent crisis in the north-eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo (which is an area of Catholic majority) remains an open wound on the African continent. Why can this situation of continuous instability not be overcome? Is it only a problem of the struggle to exploit the immense natural resources?

TURKSON: The struggle for resources is an important factor in the crisis, but is not the only one. Another factor is the lack of infrastructure such as roads or bridges: in a country so large, this means the central power is very distant and slow to take action. And then the various tribal and ethnic affiliations are a further element of instability when, partly because of the interferences of external forces in Congo, they are no longer able to find a balance between themselves. Part of the Congolese people, in fact, consider themselves Rwandan or Burundian. This is a common problem in many parts of Africa, where borders divide tribes, ethnic groups or homogeneous groups by history and traditions. The same thing happens with us here in Ghana: there is a village along the border with Togo in which a road is the dividing line. The villagers who are on one side of the road are Ghanaians, the other ones Togolese. With us it is just a bizarre situation, but in the area of Kivu, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, it has taken on dramatic aspects. Also because those who want to make away with the immense natural resources of the area, whether gold or diamonds, timber or coltan, have every interest in a state of chaos reigning permanently. When there is anarchy, confusion, even a small group of armed men can terrorize entire villages, open illegal mines, carry off everything. Only a strong central government can solve the situation piecemeal.

![Congolese Catholics during the Palm Sunday procession [© M.Merletto/Nigrizia]](/upload/articoli_immagini_interne/1279200004410.jpg)

Congolese Catholics during the Palm Sunday procession [© M.Merletto/Nigrizia]

to make huge holes on the surface of the ground, wiping out the forest. Nobody cares if one day instead of forest and farmland we will have only large empty craters because the government needs financial resources urgently and whatever brings money in the short term is preferable to long-term projects.

Because of this the Holy Father’s Message for peace this year, which speaks of solidarity with the environment and solidarity between the present and future generations, is very real and has political, social and economic implications very much felt in Africa.

Ten years ago, in 2000, there was a great campaign for the cancellation of the foreign debt of developing countries. With what results?

TURKSON: Debt is not the biggest problem: if they cancel our debts but we don’t have the means to produce goods and merchandise, we’ll never be able to create capital. We’ll get into debt again.

But right now the African countries can barely pay the interest, without ever managing to pay off the debt...

TURKSON: It would be more to the point if the governments of African countries increased productive and industrial capacity, because if we continue just to sell raw materials or unprocessed products we’ll never succeed in creating a strong economy and always be strangled by debt. Ghana, for example, is among the largest producers of cocoa in the world, but how many chocolate factories are there in Ghana? We grow tomatoes in abundance, but how many canning factories are there? It’s mainly from the manufacturing industry that wealth and stable development can come, but it’s precisely there that Africa is very weak. Only if we convert ox leather into shoes will we emerge from this vicious cycle of loans and interest.

At the Special Synod for Africa Pope Benedict XVI described the continent as the healthy lung of mankind. But what can Africa give the world?

TURKSON: The Pope was referring to Christian, religious and human values of Africa and said that we must be careful not to let this lung of humanity grow sick. It is a healthy lung when it looks to those values of the Evangelium Vitae that Pope John Paul II talked about; and the source of disease is secularism and relativism, from which Africa, so far at least, seems safe, even though we live in a globalized world and there are many threats that come to us in ways that, in themselves, are very positive. For example the Internet, through which everything reaches our young people and without any mediation. The Net brings many fine things, but you can also access sites that show you how to build a bomb and incite hatred.

You are very attached to Ghana and Africa, so much so that they say the Pope had to struggle quite a bit to persuade you to come to Rome. What of your experience as pastor have you brought with you?

TURKSON: I think I did the minimum I had to do in Cape Coast, by God’s grace and help. I was the successor of a very famous and much loved archbishop, John Kodwo Amissah, the first native archbishop of Ghana and perhaps the first African archbishop in all West Africa. He was a key figure in the political process that would have led to independence from England. I remember that at the time of my ordination, they asked me whether I felt cut out to succeed such a charismatic figure and I answered with an old saying that the only shoes I wear are my own because the others may be either too large or too small. Everything would depend on what the Lord would allow me to do. Anyway I was there from 1993 up to 2010, and fundamentally I tried to do two things: invest heavily in training priests – we have a good major seminary with capable teachers and many priests come out of it – and seek to involve young people, through initiatives also related to school, to bring them back to the Catholic Church.

Your father was Catholic and your mother was Methodist. How did your priestly vocation arrive?

TURKSON: My mother was a Methodist but converted to Catholicism when she married my father. The story of my vocation is very simple. Maybe every priestly vocation comes out of an apparently trivial reason, but then grows and clarifies in the seminary. A vocation is a bit like the starter mechanism of a car, the spark that starts the engine, and the story of my vocation is something similar. The original reason why I entered the seminary was the figure of a Dutch priest who came every two months to celebrate Mass in the small town where I grew up. Dad was a carpenter and ours was a small town near a manganese mine. There was no resident parish priest and I remember this priest who came now and then, he would sleep in the church, and in the morning was always there prompt waiting for people to come to Mass. I was struck by that, and later, when I reached secondary school age, I asked to join the minor seminary. I always tell the seminarians: the story of our vocation begins with something very small, but the seminary, as I mentioned, is the place where the vocation grows and becomes clear.

![Turkson speaking with Pope Benedict XVI as president of “Iustitia et Pax”, 26 March 2010 [© Osservatore Romano]](/upload/articoli_immagini_interne/1279200004441.jpg)

Turkson speaking with Pope Benedict XVI as president of “Iustitia et Pax”, 26 March 2010 [© Osservatore Romano]

TURKSON: We have a proverb that says: ‘If someone takes care to see your teeth grow, it’s up to you to take care of him when he loses his’. Europe brought us the Christian faith and we welcomed it. And the more alive that faith is the more grateful we are to those who brought it. Out of that gratitude, if now in Europe or the US a church is likely to close due to a lack of priests, we are ready to help keep it open, always hoping that with the help of the Lord, things will change. In Ghana, there is no longer any missionary order, apart from some native Franciscans, and two or three American Jesuits who teach in our seminary, however, there are many Ghanaian priests throughout the world.

The social encyclical of the Pope’s Caritas in veritate, on the guidelines of which the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace is working, was published in a particular historical period when the global economic crisis highlighted the excesses of a financial system without regulation and the injustices resulting. Almost a year after its publication, is the encyclical today a useful tool for thinking how to get out of the crisis?

TURKSON: As we know, Caritas in veritate was drafted in view of the fortieth anniversary of Populorum Progressio and its release was delayed so that it could be recast in the light of the crisis that had hit financial markets. Whether it is useful or not is up to the reader’s judgment, but the intent was not to provide a new economic recipe, but rather to stress the need of introducing mankind itself as the basic principle of economics, of the financial system but also of technological progress. Development that doesn’t help and encourage the development of the person can’t be considered true development. So it was a call to humanize the economy and then, since the world is becoming increasingly globalized and no one country can tackle the situation alone, the Holy Father asked whether it wasn’t time to develop a world body to steer globalization. I know that some people in the US have criticized the Pope accusing him of wanting to be the spiritual leader of a world government, but that’s nonsense. All one has to do is read what is happening in the world these days: nobody is strong enough to face these phenomena and these crises alone.